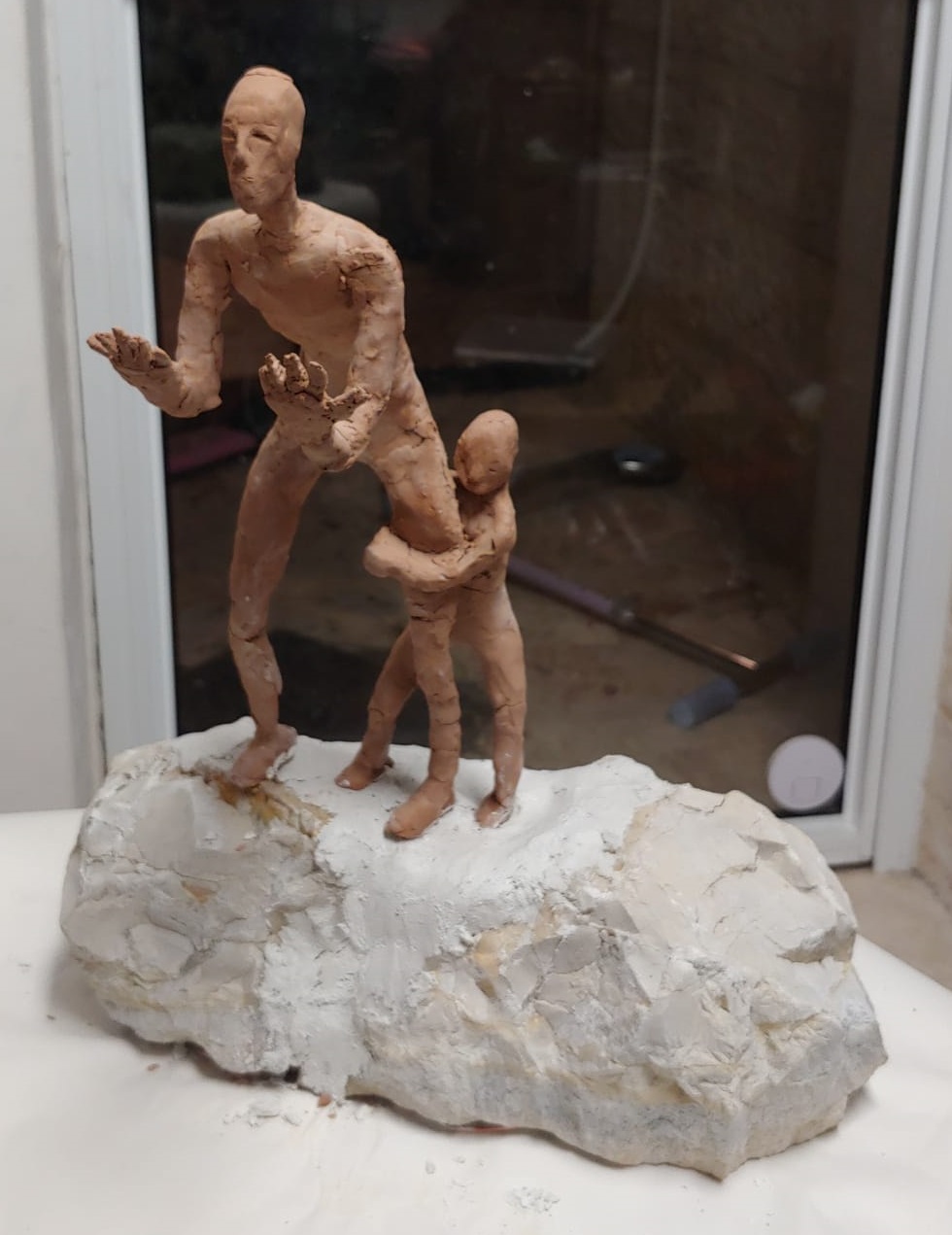

נודה-משכן (Oct 7th Statue)

Only read the below if you want to know what I was thinking when I formed this statue. It might be more meaningful for you not to know what I was thinking. I’ve already found that people see things in it that I did not intend (but do not regret).

I created this statue this week as a follow-on to my write-up of the Mishkan (Tabernacle). For a less detailed version of that write-up you can go here. In my reading the basic idea of the Mishkan/Tabernacle is that it embodies the relationship between the Jewish people and G-d (not a relationship exclusive to Jews, just a particular one). That relationship isn’t represented by massive edifices or projections of pride, but by symbolism that mingles the two. In addition, the monument that is built isn’t a memorial to those who died in Egypt or a triumphant statement of victory, but instead something that focuses on that divine relationship. It has a corollary in the Kaddish prayer, which does the same.

I wanted to make a ‘modern Mishkan.’ So, first, I represented the Jewish people as having children. Israel is the only nation where people have many children even though there is both a pension/savings system and birth control. Israeli Jews of all stripes, including the fully secular, are above replacement rate. So there is a child. Together with the limestone base (retrieved from a hillside with my bike), they represent the people in their land.

But how do you represent the relationship? That comes from the final lines of the thrice-daily Modim prayer (prayer of thanks). I translate it a bit differently, but here is my understanding:

We will give thanks to You and recount Your praise,

for our lives which you give in Your hand,

and for our souls which find accountability/meaning in You,

and for Your challenges that are with us every day,

and for Your wonders and goodness at all times— evening, morning and afternoon.

Unpacking that, the sculpture is formed from earth-colored material (not actually clay, but this is easier for me to work with). It alludes to G-d forming man of the dust of the earth. I was going to paint gold onto the palms and a bit of the face of the man – to reflect the accountability and meaning of the divine intersecting with the human. But it didn’t look right on a trial, so I didn’t.

The challenges are represented in the man’s body and expression. He is impossibly gaunt and his face is one of near-anger that is largely bereft of understanding. He has reason to be angry, and yet he is still calling out to G-d. For her part, the child is frightened, holding her father so tightly that his leg is compressed unrealistically. She is also fuller in form, being protected by her father.

Near the end of the Five Books, there is a poem (Ha’azinu). It opens with the phrase: כִּשְׂעִירִ֣ם עֲלֵי־דֶ֔שֶׁא. It is often translated as “storm winds upon grasses.” The improbable, leaning into the storm wind, angle of the sculpture is meant to capture these winds – rough and challenging headwinds that are somehow part of how G-d forms us.

Finally, the evening morning and afternoon represent G-d’s presence in our existence. Despite all the suffering, we are still here. We are still bowing, three times a day and saying the thousands of years old Modim prayer. That itself is evidence that G-d will fulfill his promise to our forefathers – a covenant formed because they loved His name (from the opening of the Amidah prayer). Likewise, if we love the name of G-d, G-d will ensure that our lives have meaning beyond our own time on this earth.

The people, land and G-d come together in one more way. Each of the statues is held down, at an improbable angle, but a wire – a thin but strong root that runs into a crack in the rock (I borrowed the idea of Michael Jackson’s anti-gravity lean of all places). Through this, I’m alluding to the sin of the spies. The Jewish people say they are grasshoppers, with no home. They can’t stand up against the Am Ha-aretz – the people of the land who are a part of the land. Later in that reading we are told to wear Tzitzit. The word Tzitz is used to mean blossom in the next reading. It suggests that we will not be of the land but we will be G-d’s trees in the land. The roots weaving into the stone represent this as well.

Very poetic. I had thought the child was holding back the father from confronting danger, but no.

It is art, you can indeed interpret it in your own way 🙂