Parshat Yitro: Highlight or Letdown?

Podcast and transcript below…

This week, I’m only doing 4 faces of Torah: inspirational, political, trivial and structural.

Enjoy.

Inspirational

When Yitro comes to visit, Moshe is famously spending all day judging. There is no administrative state and, as far as we can see, the people aren’t moving. They are learning, tiny bit by tiny bit, from Moshe’s judgements. But they haven’t taken a transformative step forward. They haven’t even brought an offering to Hashem. Yitro comes and brings an offering of his own, but the people seem to lack the standing to do so.

Nonetheless, they seem to leap forward in this reading. They go from being recently freed slaves being taught through deprivation and violence to being a people ready to receive the Ten Commandments.

What happens?

The answer, of course, is Yitro.

In years past, I’ve shared a simple idea. Yitro had Moshe establishes judges throughout the people. Judges of 10, 50, 100s and thousands. By becoming judges – by having the act of judgement dispersed among the people, the people learn responsibility. Instead of being dependent on Moshe, they can be dependent on one another. The character of the nation thus rises – and they are ready to receive the Ten Commandments.

I want to take this idea a little further.

Yitro tells Moshe to find specific kinds of people to be judges.

אַתָּ֣ה תֶחֱזֶ֣ה מִכָּל־הָ֠עָם אַנְשֵׁי־חַ֜יִל יִרְאֵ֧י אֱלֹקים אַנְשֵׁ֥י אֱמֶ֖ת שֹׂ֣נְאֵי בָ֑צַע וְשַׂמְתָּ֣ עֲלֵהֶ֗ם שָׂרֵ֤י אֲלָפִים֙ שָׂרֵ֣י מֵא֔וֹת שָׂרֵ֥י חֲמִשִּׁ֖ים וְשָׂרֵ֥י עֲשָׂרֹֽת׃

You shall also seek out from among all the people men of character (Chayil) who fear God, men of truth who hate corruption. Set these over them as chiefs of thousands, hundreds, fifties, and tens,

Going back to Parshat Lech Lecha, Hashem promises Avram that his descendants will be enslaved. The promise follows Avraham’s simply question: “How can I know?” As we’ve discussed, the people need to trust – even in the face of what appears to be evil and loss. They’ve learned this, or at least it seems they’ve learned this, from the Exodus itself. But they are no Avram. We can see Avram’s greatest immediately before his question that leads to their enslavement.

Avram goes to war with the four kings with only 318 men. He shows he is a man of character and courage. An Ish Chayil. The word is later used to refer to a soldier – including in modern times.

Avram gives 10% of the spoils of his war with KedarLaomer to MalchiTzedek the King of Shalem (later Jerusalem). He acknowledges Hashem’s role in his victory. He is a man of truth.

When the King of Sodom suggests that Avram get the rest of the spoils, Avraham refuses. Famously, he says “I will not take anything from a thread to a sandal strap from you – lest you say ‘I have made Avram rich.’”

Avram shows that he hates corruption.

All that was missing – although Avraham acquired it personally through the Akeidah (the Sacrifice of Isaac) – was Fear of G-d. His descendants acquire this fear from the Exodus – including the symbolic reenactment of the Akeidah with the Passover Offering.

When Yitro suggests that Moshe find men of character (Chayil) who fear God, who are men of truth who hate corruption and then make them judges of the people he seeds the people not just with responsibility, but with all the attributes of Avraham.

In a way, they go full circle, seeming to achieve the heights as a nation that Avraham himself struggled to achieve as an individual.

In our time, Avraham’s challenge – on both a personal and a national level – remains. But Yitro provides us with the first steps towards resolution. We must form our nation around people of character and truth who fear God and hate corruption. When we do that, when we make those people our leaders of 10 and 50, of 100 and a thousand, then we too can be transformed and realize the fullness of our freedom.

Political

The political concept this week is an extension of what we just discussed. Yitro brings judgment before there is law. Yes, a case law – built around the hard cases – is established over time by Moshe. But the people judge while this process is in its very early stages. It shows us that a society isn’t built on law in a vacuum. Law must be built on a society that already embraces responsibility. It is responsibility that comes first. In a recent podcast, I called it civil society. A society that has this sense of responsibility woven within it is a society that can be free, that can be lawful, even without defined law. But a society with perfect laws can not succeed if the people within it are not responsible.

In today’s world, civic responsibility seems to focus on the ideas of ferreting out the shortcomings or sins of one’s political opposition. If battling against tyranny, this kind of civic responsibility breaks down the mechanisms of enslavement by uncovering and exposing them. This kind of civic responsibility has its place. There is courage and hatred of corruption within it. I encourage you to watch Alex Navalny’s movie if you have a chance. But there is an even more fundamental form of civic responsibility. Not the kind that focuses on the lives of nations, but the kind that focuses on the lives of individuals, families and neighborhoods. The judges of 10, 50, 100 and even a thousand are those who weave the fabric of responsibility into our societies.

The focus on nations can protect and even enable the future. In a way, the focus on nations is like clearing a field and preparing it for planting. It can create a fertile reality for social growth.

But it is the focus on individuals, families and neighborhoods that actually builds the future. These are the seeds of the field and they must be planted and nurtured – one by one.

As much as we might enjoy focusing on the grand scale – and pointing fingers at the evils of our opposition – greatness is actually built from the smallest of pieces.

It would behoove us, in these troubled times, to remember that.

Trivial

#1) Yitro says something remarkable and almost nonsensical.

“Blessed be the LORD,” Jethro said, “who delivered you from the Egyptians and from Pharaoh, and who delivered the people from under the hand of the Egyptians. Now I know that the LORD is greater than all gods, yes, by the result of their very conspiracy upon them.”

The subject and object of this last part of the sentence is unclear. Whose conspiracy against whom? We can understand by understanding a bit more about Yitro.

Yitro came from a polytheistic world. Each natural force was a god. When the gods all acted together against Egypt, they conspired. As any good god manipulator would know, gods are to played off one another. They don’t act together. If they do, as they did, then the LORD is greater than all the gods.

#2) Yitro’s laws are the only laws given in the Torah that do not come from G-d. They don’t even come from the Jewish people. And yet they serve as the basis of the entire society. There is a lesson here – that responsibility, like creativity, can’t be commanded. It must come from within us.

#3) Yitro seems to leave, but then shows up again later. I see him almost like Solon – the Athenian Law Giver. Solon wrote the Athenian Constitution and then, legend has it, he left for 10 years. He had to leave so that people followed the laws, not him. They people had to take responsibility. Solon only cleared the field, the people had to plant it. When both Solon and Yitro return, they are but citizens in a society they had a hand in defining.

#4) Yitro is the Midianite priest. The role is a little different than we might imagine. His own daughters are harassed by shepherds when we see Moshe coming to Midian. This is not a sign of deep respect. As we’ll see later in the story of Bilaam, priests in Midian are there to manipulate gods. Gods are to be played off of one another. Priests are simply tools of kings, designated to play this role. They do not have some kind of inherent respect given to them. In a way, priests bring the gods down to people instead of raising the people towards G-d.

We see Yitro’s position in his arrival. Yitro doesn’t just show up at Moshe’s tent and say “Hey, how ya doing?” Instead, he comes to the camp and then sends word that he is there with Moshe’s wife and two children. He says, “I, your father-in-law Yitro have come to you.” It is like he is addressing a King and he must request an audience and give a reason for being there. Moshe – by contrast – comes out, bows low to his father-in-law and kisses him.

Each of these men has to learn from the other. Moshe has to learn the administrative and formal gifts his father-in-law has. Gifts he must have as a servant and tool of Kings. And Yitro has to learn, as we discussed above, that G-d is in charge and Moshe is no King.

#5) Yitro suggests that the judges pass cases up based on their size. Moshe should get the big cases. Moshe changes this. In his rendering, he brings the hard cases before Hashem. We see this in modern jurisprudence. Most of the time, the most important cases before the Supreme Court do not involve vast sums of money or powerful people. These are not the cases that define law. It is the hard cases that rise and end up setting the precedent for all other laws.

Structural

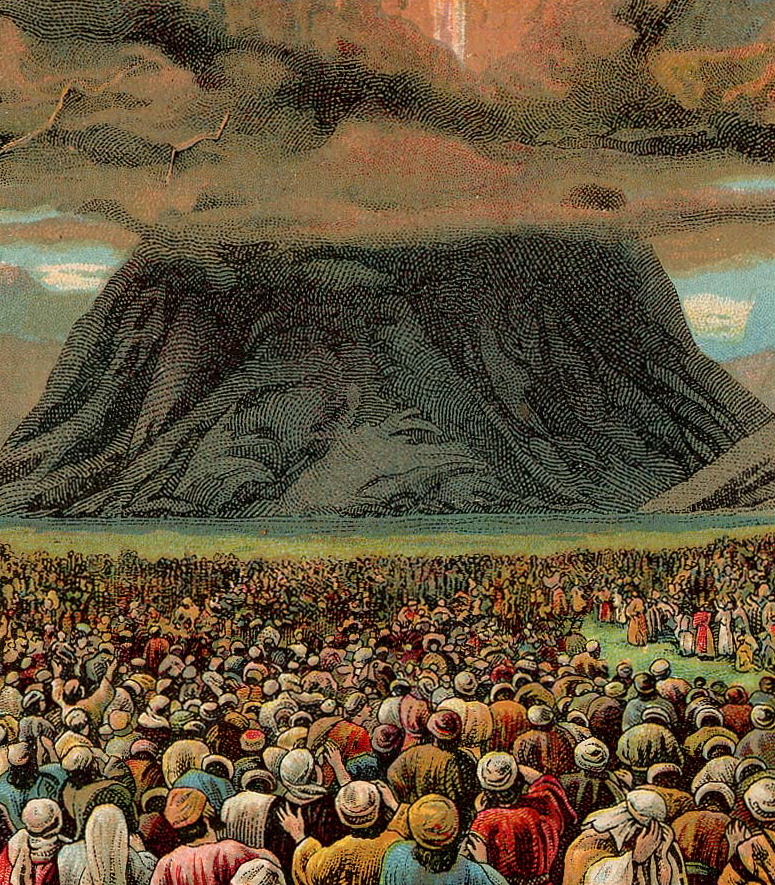

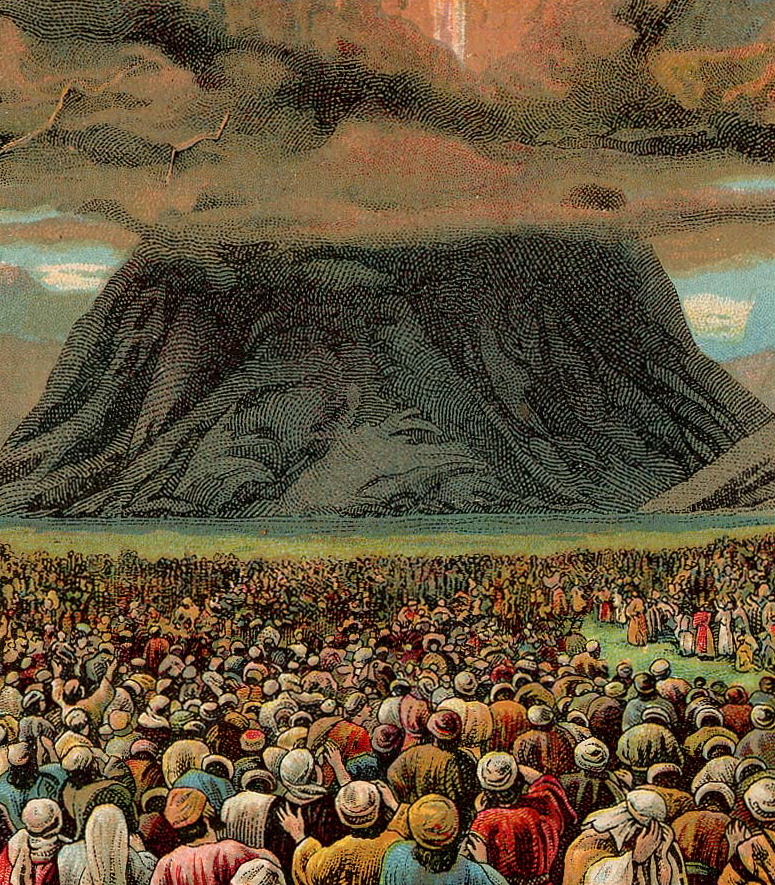

After the arrival of Yitro, we come to Har Sinai – Mount Sinai. Hashem promises that if the people keep His covenant, the people will be a treasured nation, and a Mamlechet Kohanim v’Goi Kadosh (a Kingdom of Priests and a Holy Nation). Hashem sets up the revelation on Har Sinai. But an important part of the revelation seems absent from the story that follows.

Hashem says – after warning the people not to ascend or touch the mountain – “Bmesech Hayovel [the people] may go up on the mountain.”

But they never do . Not long afterwards, Hashem walks back from the initial idea that the people will come up. Then he suggests that only the priests will come up. And finally, even they are excluded.

It seems like this mysterious Meshech HaYovel never occurs.

So, what is this mysterious Yovel? What is missed and why is it missed? What purpose do the Aseret Hadibrot (the Ten Commandments) have in its absence?

Mesech Haovel has two words. The second is Yovel. I discussed the Yovel in my special podcast on Torah economics last week. It is the 50th year -the Jubilee. A year in which property is returned – in recognition that it isn’t really ours. The word means to ‘acquire’. Not create, but acquire. And it often has negative associations. The sons of Lamech all acquire and it leads to the breakdown of society. We are meant to be creators, not just acquirers.

But the year of the Yovel is something else. We acquire then, through no effort of our own, and it is the holiest of times. There is the normal sabbatical year, which is hard to accept economically. An entire year without work, without planting, would seem to be almost impossible. But the Yovel is the 50th year – it means two years in a row without planting the 49th and the 50th. To do this, to celebrate this, requires incredible trust in Hashem. But it also implies a time in which we step outside of the normal course of human existence. Ownership becomes a forever thing – based on our relationship to the timeless G-d.

Critically, the Torah makes clear that the Yovel only works if you believe it will work. The shmita, the sabbatical year, is the same thing: if you believe it will work, then you will have a bounty prior to the Yovel or Shmita that enables it.

The Yovel is thus the ability to simply receive – and to be connected with the timeless divine – by stepping outside of normal time. But it requires incredible trust to work.

With this context, we can have a greater understanding of it in Hashem’s earlier declaration. The people are to be a treasure to Him. They are to be a Mamlechet Kohanim v’Goi Kadosh – a Kingdom of Priests and a Holy Nation. As we’ve discussed before, Holiness and Goodness are almost entirely separated within the Torah. Goodness is the result of creation, Holiness of rest with the timeless. They only intersect, indirectly, in the building of the Mishkan – the creation of place of holiness.

A Holy Nation does not create. Humankind creates, but a Holy Nation which is a Kingdom of Priests serves as an intermediary to the divine for the rest of the world. I think this is what the Yovel – this word – is suggesting. There is a possibility of a fundamental transformation of the reality of the people.

This concept is strengthened by the word Meshech. Meshech is a very common modern Hebrew word. It means to continue: Hemshech. But it is used only rarely in the Chumash and it means something very very different.

The first time is when Yosef is gathered by the Midianites. The Midianites Meshech and then pick him up. It transforms him from a free man to a slave. The second time is when the people are supposed to get the Pascal lamb. That action transforms the people from slaves to actors – albeit very limited actors – in their own right. The third use is here. They aren’t being freed or enslaved. Instead, the word is suggesting another fundamental transformation.

We can lay out their status, their reality, in a line. In Egypt, they were slaves. They couldn’t think beyond the moment. Think about the bitter herbs – you eat them and you can’t think beyond now. Then they were freed and, as Moshe points out a few verses later, they can think about their own grandchildren. This is Meshech.

This Meshech is to be another step.

Instead of doing what humanity normally does – creating our own future in the face of loss and destruction – we can step outside the world in which we must create to acquire.

Instead, we can enter a reality of Yovel. We can be connected to forever and be provided for in a world without evil. We can think about forever, not tomorrow.

But it doesn’t happen. We know it doesn’t happen, because Hashem says that when it does they can ascend the mountain. And they are never allowed to ascend the mountain.

The question is why? Very few things happen as Hashem shifts his position. Nonetheless, that process of exclusion is critical to understanding why we did not in that moment become a Kingdom of Priests and a Holy Nation – and why we are still struggling to achieve that reality today.

At first, the people are all supposed to ascend. But then only the priests are allowed to ascend. The people only carry out one action between those two points. When there was thunder and lightening and a thick cloud and the shofar was loud – they trembled. The word is chared – the same root as Haredi. They were terrified. Fear of heaven – the ability to do what you can’t understand – implies trust. But Chared shows a lack of trust. Just like the 50th year of the Yovel requires trust, this Yovel requires trust.

Trust, not terror.

This trust is a core – and yes, frightening – message of the entire slavery. Avraham can not quite trust when Hashem puts his inheritance in the context of his own brother’s death. The people cannot trust when Hashem has allowed them to be enslaved by a genocidal Pharaoh. But here, they seem to be on the cusp of trust. The Az Yashir, their experience of redemption, seems to show that they can understand that it all has a context; that Hashem uses both the good and the evil in service of something greater. In service of the Holy. The Ma’an reinforces this concept. We can trust, day by day, in Hashem providing for us. And that is connected to Shabbat – the satisfaction of interacting with the timeless.

But this trust can’t coexist with terror. Terror reveals that, in fact, they do not trust.

So, the people are excluded.

But Hashem doesn’t exclude all the people. Instead, he says the Kohanim – the Priests – can ascend. It is here that we get the clearest definition of what a Kohen here. The Kohanim are those who come close to G-d. Hashem says that Moshe should tell them to sanctify themselves and then they can come up. If they do not sanctify themselves then Yuk-Key-Vav-Key – the timeless G-d – will burst within them.

Then, only 2 pesukim later, Hashem says even the Kohanim cannot come up.

What happens in between? What changes?

Just one thing. Moshe says:

“The people cannot come up to Mount Sinai for you warned us saying: ‘set bounds around the mountain and sanctify it.”

On the one hand, Moshe is saying ‘I don’t need to tell the people this again, they know.’ But there is something else here.

I grew up around a fair number of drug users. Although I never dropped acid myself, a relative who did literally hundreds of hits gave me simple advice for going on a trip of my own: never lose track of time. If you let go of time, you might never come back.

To me, this is related to this concept of the timeless bursting within the Kohanim who have not sanctified themselves. The timeless bursts within those who have not sanctified themselves and they are destroyed by it. But if they sanctify themselves – if they dedicate themselves to the timeless divine – then they can survive.

Instead of trying to comprehend and grasp the timeless on their own terms, which will destroy them – they can approach Hashem on His terms. They can come close to G-d as a part of G-d – having dedicated themselves to Him. Then, through this act of trust the timeless will become a part of them – and not destroy them. It will be compatible with their sanctified selves.

To put it another way, they can go on the trip and lose track of time because G-d Himself will protect them on their voyage.

But what does Moshe say? Moshe says the mountain has been sanctified by setting boundaries around it. He suggests that the process of sanctification is an act of separation. We often separate in order to dedicate. It is often a step on the path to sanctification – but it is not sanctification itself. With Moshe’s definition, the Kohanim might image the purpose of sanctification is separation from the people rather than integration with Hashem. This misunderstanding means the Kohanim cannot approach. They are not ready to surrender themselves to the timeless and so the timeless will burst within them.

They are ready to be distinguished from the people, not dedicated to something greater.

While many people read the giving of the Ten Commandments as the ultimate highlight – I read it as something else. We had a chance to be transformed. To enter another reality – beyond the world of freedom. We had a chance to trust in Hashem, come up the mountain, and become a part of the timeless.

But we could not do it. First, because our terror meant that we lacked trust. And second because we did not understand the true nature of holiness.

In both cases, we did not surrender ourselves to Hashem – accepting that which we can not understand in order to become a part of a reality far greater than ourselves.

The Ten Commandments – from this perspective – are not about the realization of ultimate heights. Instead, they are about laying the groundwork – the very first steps – on the long road to embracing the perspective needed to become a Mamlechet Kohanim v’Goi Kadosh – Kingdom of Priests and a Holy Nation.

There is no criticism here. Hashem does not criticize the people. Moshe does not criticize the people. There is only possibility and possibility which can still be realized.

Structural Part II

At the beginning of the Parsha, we saw the importance of law and procedure to enable Moshe to become a leader. In a way, the laws that come with – and follow – the revelation on Har Sinai are a parallel to this.

In order for the people to rise, just like Moshe, they need structure. They need law.

They can’t simply trust, they have to grow into trust.

Read this way, the first laws given – the Laws of the Ten Commandments – are not the highest laws. They are the most basic. In a word, they are saying: don’t break anything.

There are many examinations and breakdowns of the Ten Commandments. I’m going to focus on just one that explores this idea – the idea of not breaking anything.

In analyzing the Ten Commandments, the second ‘tablet’ of laws (those clearly concerning human-to-human relations) can provide quite a bit of insight to the first set. In essence, we have the same set of commitments to G-d as we do to man.

First, you shall not murder is paired with the statement of G-d’s redemption of the people from Egypt. The Exodus was a statement of G-d’s total power. It gave Him life among the Jewish people. Our recognition of the Exodus maintains His presence in a most direct sense. To deny it would be to terminate G-d’s life among the people.

You shall not commit adultery is paired with not worshiping other things.

You shall not steal is paired with not ‘lifting’ G-d’s name in vain. The only thing in this world that is clearly G-d’s property, and nobody else’s, is His name.

You shall not bear false witness is paired with the Shabbat (Sabbath). For the Jewish people, the Exodus is the source of our connection to Hashem. But the Shabbat speaks to His connection to the world at large – His position as Creator. Failing to keep the Sabbath would be an act that would falsely damage Hashem reputation.

Finally, honoring parents and covetousness are paired. If we are covetous, we will deny our neighbor’s peace. If we dishonor our parents, we will deny G-d’s. By honoring parents, we maintain Hashem place in our community over generations. And by honoring parents, we provide a basis for our own place in the flow of human life. By honoring our parents, we can extend the ripple of their lives and mix it with their own. It not only gives G-d peace in His relationship with the people, it gives man a firm grounding in his own past.

In these laws we have a responsibility not to take: life, relationships, property, reputation or peace from others. These laws aren’t about high moral, ethical or religious objectives. They are about establishing a baseline above which everything else is built.

At the end of this reading, before getting into the laws to govern society directly, there are four critical commandments given.

- The first is the commandment not to make images of G-d.

- The second is the commandment that we make an earthen altar to bring offerings to Hashem and He (or She) will bless us.

- The third is that if we make a stone altar, we must not use a tool.

- Finally, we are commanded not to have steps leading up to the altar, so that our ervat is not exposed.

These laws seem like an odd appendage – randomly tacked on. In reality, these three laws are an overview of how our relationship with G-d is to be defined and built. They are an overview of how we will achieve holiness in the future.

The commandment not to make images of G-d is a reminder that, although Hashem is separated from our community, our objective is a direct relationship. We don’t worship intermediaries.

In both of the commandments of the altars, it is clear we don’t make an altar of human materials. There is no copper or gold or even wood here. There is earth and stone. A tool is forbidden because it would profane the altar. The word is chilul. Any act of creation or destruction on Shabbat is a chilul. We separate creation and holiness. It isn’t that chilul is bad, it is often good, it is just that we separate it from holiness. We bring korbanot on those altars. The word comes from the root karov – or ‘draw close.’ If we want to draw close to Hashem – if we want Him to come and even bless us – we do it on timeless basis. We do it in a way unsullied by human change.

Finally, the commandment not to have steps leading up to the altar is given so that our ervat is not exposed. Ervat is often translated as nakedness. But it has a broader meaning. In the story of Yosef and his brothers, Yosef accuses the brothers of being spies – trying to find the ervat of the land. They are looking for faults, for weaknesses. The Kohanim have pantaloons to cover their bottoms so covering their weakness (in terms of waste or reproductive areas) isn’t the point of these stairs. Their physical ervat could be covered with a longer or more garments. This ramp is about something else. I believe it is about how we ascend to Hashem. If we ascend stairs, it highlights the levels that separate us. It highlights our weakness and limitations the he face of the timeless divine. But ascending a ramp – a continuum – covers our weaknesses. It hides our distance from true timelessness. And it tells us that when we want to approach Hashem, we do it on His terms. We don’t highlight our weakness. Instead, we cover it so we can raise ourselves up instead of bringing Hashem down.

These laws thus show us:

- We seek a direct relationship with Hashem

- That relationship is built on timeless, and thus intrinsically holy, means

- When we draw close to Hashem we do it by raising ourselves up

Bringing these laws together and we see that the Ten Commandments are about not breaking anything, while the laws that follow give us the first guidelines on how to go beyond that – and establish a relationship with Hashem.

Conclusion

If any of the ideas in this episode help you or appeal to you, then share them. You don’t have to share them in my name; go ahead and steal them and make them your own. They’ll serve their purpose just a well.

Thank you for listening and Shabbat Shalom,

Joseph Cox