Ki-Tisa: The Transformation of a People

The face of G-d, a divine river, foreshadowing and more! Dip into the ancillary parts of this Torah portion to discover how and why the relationship of the Jewish people and G-d is fundamentally transformed.

I thought, after the speech I shared as the first podcast, that I’d have only a few small thoughts to share. I went back to my notes and saw how very wrong I was.

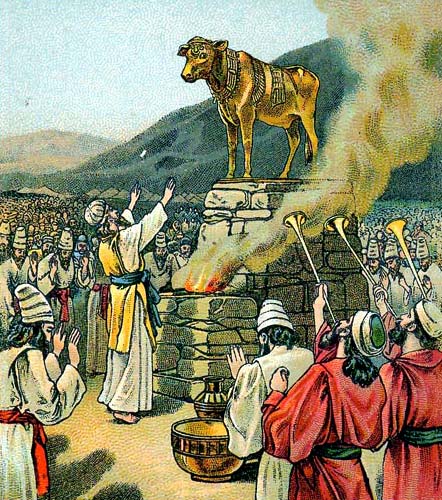

I’m going to go through the Parsha in an almost linear way – trying to capture the shifts and changes that occur in this momentous reading as I do. I’m going to skip (for the most part) the sin of the calf itself – that I discussed in the speech I delivered earlier this week. If you want to listen to it, it was an important speech for me. It was the speech I gave the week before the death of my mother.

I do want to start with the broad shift that occurs in this reading and kind of capture it to give you a framework as we step through the individuals portions. We start off with a reality in which our feelings are controlled and placed within a general national framework – one defined by G-d. We don’t offer incense – which represents emotion – until everything else is ready. And we are warned not to offer strange incense. Then we commit the sin of the calf, the sin of collective self-worship. In order to save us from condemnation Moshe shifts our relationship. We were intended to be a people whose testament to Hashem’s redemption will serve as evidence of G-d’s working in this world. When we ascribed that redemption to ourselves, that framework disappeared. We’re no longer able to testify to G-d rescuing us from Egypt when we rescued ourselves from Egypt.

Moshe transformed us to being a people whose treatment by G-d would itself be a testament to His presence. If we are blessed when we serve Hashem – or are being redeemed – we will be a witness to G-d. And if we are cursed when we fail to serve – then we will be a witness to G-d.

With this shift, we acquire national blessings and curses. The whole idea of cursing the nation didn’t exist before this reading – it was only vaguely hinted at with the mistreatment of the widow and the orphan.

With this shift, the nature of our relationship changes in other ways. No longer is it distant and controlled and firmly within a divine framework. Now we, led by Moshe, have to take the first step. The Mishkan we build after the sin of the calf is thus a very different structure to the one designed by G-d before the sin of the calf. Yes, physically it is similar but the underpinnings are very distinct.

Let’s step into the readings.

The completion of the mishkan’s design is realized with the uniform donations and their textual connection to three items: washbasins, scents and oils. The kohanim wash their hands to eliminate outside influences on their actions (hands) and will (represented by their feet) prior to service. The articles used for this preparation must themselves be free of those influences – and so the money for them must be commanded without any personal influence or input.

This is the reality of a divinely-driven service.

The scents seem to build a meta-mishkan of smell – a Tent of Meeting. The emotional connection of the Tent of Meeting is so fundamental that sight and hearing are insufficient. We need smell, the sense most able to directly touch our emotions. But the smell and its emotions must be national, not personal. And thus, they are built on the uniform donations.

Finally, the oils fuel the Menorah’s fire; the representation of divine energy. But they aren’t our oils, they are oils which are national in their character and divinely connected.

With these three items, the community become like kohanim – filling a timeless role as members of the brit rather than acting as individuals.

With the building of the mishkan, it is time for the people to be accounted for on their own merits – or reckoned. This is what was promised in Yosef’s dream – we would go out and have our heads lifted up before our King. Being reckoned (the word is Pakad) is dangerous; on close inspection people might deserve reward, or they might deserve punishment. After all, despite Yosef’s hope they didn’t earn Exodus, they didn’t. They were Zochered (rescued because of a contract with Hashem which he had to honor because he made it with Avraham.) The word was not Packad; they were not rescued because of their own merits). With a uniform contribution, they stand together in service to G-d. Just as gold represents divinity, silver represents the human reflection of the divine. When we are counted by our silver half-shekels our divine souls are counted – the half of our souls which are divine – but our human distinctions are not reduced to numbers. The risk of being reckoned is mitigated. Our divine souls – pure and holy – are what is counted. The word Kapar – for atonement – means a cover or a seal. Putting our divine selves forward and having those parts of us counted seals away our more human failings.

I’ll add a few quick notes to the egel and the punishment that is related to it. If you want to know why I think it was a case of national self-worship, listen to the other episode. I do want to mention that the act of self-worship had warning signs prior to this reading. The people say at the Song of the Sea: Azi v’Zimrat Ya Our strength and the song of our Lord. They ascribe some aspect of their redemption to themselves. Then, two readings later, they build pillars – one for each tribe. This suggests some great honor for the tribes, almost a divine honor. And then they cast the blood of first offerings – for the first and last time – on the people and the altar alike. They make themselves a symbolic equivalent of Hashem. The egel maseicha – the molten calf – does not come from out of nowhere.

When the time for reaction comes, Moshe crushes the egel. The gold that represents its divinity is ground up. Then something weird happens. He casts it onto the face of the water. It seems the gold doesn’t sink into the water. How can this be when gold is 13 times the weight of water? Perhaps this happens because the only water in the desert is the water from the rock. The waters of Torah. Even though gold is heavier than water, it floats. The waters of the Torah – the waters of Hashem – cannot accept the egel. When the people drink this gold, which represents their collective divinity – they are converting what was spiritual – may not have been from Hashem, but it was spiritual – into something physical. Most of the Torah deals with making the physical spiritual, but this is a rare example of the inverse occurring.

In the negotiations that occur immediately afterwards we see some very strange actions by Moshe. Moshe is pushing first for Hashem’s accompaniment – which wasn’t promised earlier. Hashem says “my face” will go with you. And Moshe responds: “It better!”

Why is he pushing so hard just after the Jewish people committed a massive sin? I think Moshe recognizes why the people were so distraught when he didn’t come back down the mountain. They felt frightened and out of control – and with Hashem’s distance, the feeling grows. Hashem is beyond understanding. There is nothing to touch, to feel or so smell. The people had nothing to hold on to.

We’ll get to how Moshe provides something to hold on to in a bit.

Before we do that, I want to mention that Moshe wants to protect the people above all else.

Woven into his initial demands is a phrase repeated three times in very close succession. matzati chain be-einecha,‘I find favor (chain) in your eyes’ (or a similar formula).It is acommon turn of phrase (used to refer to grace from humans and G-d alike). But it is never this common. Here, Moshe distinguishes himself by sharing his chain – his divine capital – with an undeserving people. This is a sign of Moshe’s great leadership. He sacrifices himself, here, for the people.

But he spends that political (or divine) capital on two demands. First, he has to know Hashem’s ways. He has to have something more concrete to share with the people and he needs to strengthen his ability to witness for G-d. Our own definitions limit Hashem, so Moshe asks Hashem to define himself. And second, he needs Hashem to stay with the people. They need Hashem Himself there so that they can feel what they cannot understand. They can know what they can not understand.

Blaise Pascal, a famous mathematician, spoke how you can have faith in G-d and know G-d.

Among other things, he was a rabid anti-semite, but he said some very interesting things.

One of his defenses of G-d was he would ask: “Do you love your father?”

When they said “Yes, I love my father” – assuming they did – he would say “Okay, prove it.”

This idea of being able to feel this connection to G-d is why you want to have G-d in the camp and bringing them to the land.

If they don’t have this feeling, this connection, this something to hold on to, this love to feel, then they can never be redeemed.

Hashem responds by telling Moshe, ‘you will see all my goodness,’ which is His back. If we go back to Bereshit, goodness follows Hashem’s acts of creation. He makes and then he declares that it is good. When Hashem reveals His goodness to Moshe, He hides Himself with his hand – the body part that represents action and execution. When Hashem is acting, His own actions hide his presence. But once those actions are complete, once that veil is removed, we can see and Moshe can see where Hashem has been and the goodness that He has done. Moshe is seeing is the total actualization of Hashem’s creativity in this world. The past. It is not Hashem’s face that he sees – simply that which follows him.

If we are to be G-d’s people, we must leave a trail of goodness in our wake as well.

What Moshe can’t see – what no man can see – is where Hashem is going. We can see the derech (the road) travelled, not the derech ahead. Hashem is “I will be what I will be.” Knowing what Hashem will be is outside human purview. There are many possible reasons for this. One that appeals to me is the idea that with free will, there might be infinite futures (all of which somehow fit within a divine plan). A man could be destroyed by that perception. Just imagine Moshe’s situation; he rescued the Jewish people by arguing with G-d. But what if, as suggested later on, G-d’s plan was to have him argue the whole time? How do you reconcile the time-travel style paradoxes that emerge? I don’t think you can.

Hashem next commands Moshe carve the next set of luchot (tablets). It is not a downgrade. Moshe has contributed to Torah (which is recognized in the final parsha of the Torah with the phrase Torah Tziva Lanu Moshe – the Torah which Moshe commanded us). This carving is a foreshadowing of what is to come. The Luchot are not simply handed down by G-d – we humans must play a role is establishing it. Moshe provides the physical context for the luchot, while (at least at this point) Hashem is to provide the words.

In standing up for the people and then carving the luchot and taking the first steps towards rebuilding the relationship with G-d so soon after breaking them, Moshe exhibits a remarkable recovery from anger. He demonstrates something fundamentally G-dly.

I believe this is why Hashem lets him (and us) see something of His face (al panav). Hashem Hashem, Kel Rachum v’Chanun is not just a list of 13 attributes of G-d. They are the face of G-d. They are forward-looking – after all, you can’t have thousands of generations of kindness prior to thousands of generations people existing at that point in time in the Torah. This is not just a passing wake of divine goodness. We don’t literally see G-d, but we know Him as never before. In a way, Hashem’s presence in this world is the presence of actions – represented by His good – and of values – represented by these attributes.

As a distinct nation, we should not only admire these attributes, but we should make them part of ourselves.

How might these apply today? I read this verses as: Hashem Hashem (in timeless and total words), G-d of motherly mercy (rachum also means womb) and grace, slow in anger, abundant in kindness and truth. Keeps faithful to a covenant (notzar) of kindness for thousands of generations. Lifts (naseh) the weight of sin (a’von) and violations (pesha) and destructiveness (chait). And cleansed (perfect tense of nakeh), but not cleansing the future (imperfect sense of nakeh). Reckons the sin of fathers upon sons and sons of sons – on the third and fourth [generation].

The lesson for us? Practice motherly mercy and grace, be slow in anger, be abundant in kindness and truth. Keep faithful to Hashem’s covenant of kindness and other covenants of kindness. Lift the weight of sin, violations and destructiveness from our world. Cleanse the past but do not absolve those who would sully the future. And reckon even great sins (such the shoah) on those three and four generations on – but don’t bear those grievances forever .

Imagine what it would be like if mankind adopted these precepts – particularly mankind in our neighborhood.

As a quick aside, this concept of kindness to the thousandth generation but hatred only to the third or fourth offers a solution to aanother conundrum. In Devarim, the Torah says that the forefathers loved Hashem. They got a britor covenant as a result. This brit results in a long-term promise of kindness. But in the intervening time, the Jewish people rebel. For this, we suffer terribly – for three or four generations. It is our challenge to rejoin the long-term track.

As another quick aside, I was listening to a podcast this week (the Ancient World podcast) that focused on the ancient Jewish Kingdom in Yemen. The history is fascinating – although the podcaster isn’t an expert in Judaism. Of particular interest, the persecution of Christians in retaliation of Roman Christian persecution of Jews. The persecution of Christians that occurs here – against people who were themselves not a challenge – leads to the destruction of this Jewish Kingdom by the Christian Kingdom of Axum. I bring it up because when the Yemenite Kingdom converted to Judaism, they began to make dedications to Rachman. That was the name of Hashem that they used – kindness.

Back to our Parsha. Even after the thirteen attributes, Moshe pushes again. “Forgive our iniquity and our sin and nachalat us.” What is nachal and why does it trigger an actual brit (a covenant rather than just Hashem’s promise)? As I talked about in the other podcast, It is variously translated as a possession, inheritance, valley or stream. These notes create an image of a stream flowing through and cutting out a valley; defining it, unifying it, making it distinct and, in a way, possessing it. It is that river’s valley. The river is created by the valley and the valley is created by the river. To inherit in this way is to flow and thus create a space which becomes designated for you. This is how we are to inherit the Land. We become Hashem’s nachal by virtue of Torah and his forgiveness flowing through us and defining in us a valley of Torah. But we also define the world we touch, bringing Hashem’s presence with us. Moshe points out that our valley will be stronger and more secure – our Nachal – because (the word is ki) we are a “stiff-necked people.” This requires more than a promise. For Hashem to designate us in this way, we must do our part and designate ourselves. This requires a public brit in front of all the nation.

My brother is fond of pointing out that Hashem threatens to destroy us because we are a stiff-necked people and promises to preserve us because we are a stiff-necked people. Our fundamental attributes don’t change. But despite that, the role we play can.

So there is another brit. Hashem makes the people distinct. He carves them from their neighbors. This is the reality of nachal. Then, we have a list of laws that serve to distinguish us as G-d’s people. The first set instruct us to distinguish ourselves, the second to recognize the role and gifts of Hashem and the last to protect the divine cycle and separation of loss from potential and realization. All of these laws fall into the category of goi kadosh. Hashem’s river of Holy Law distinguishes us and makes us into his valley, inheritance and possession.

Let’s dive into a bit more detail. How do we distinguish ourselves from our neighbors so we can be a testament to Hashem? It starts with not worshiping ourselves (a new prohibition against maseicha) which is directly connected to acknowledging the Exodus and the distinction made for our first born (vs. Egypt’s). We must keep Shabbos. We must dedicate our physical production from the land to our spiritual connection. Finally, we protect the cycle of physical and spiritual realization. We must not combine the spiritual realization of an offering’s blood with leavening. Leavening represents Hashem’s gifts to us – it does not represent our dedication of ourselves. It does not represent the movement of physical to spiritual. We must not allow the Pesach meat to decay. We must not shortchange the spiritual by providing second-tier or late physical produce. And we must not mix the creative potential of milk with the destruction of potential reflected in the animal’s death.

The prohibition of maseicha has (for the first time) been added to the list of inappropriate worships. This is perhaps a reaction to the egel. Hashem seems to be saying ‘Not only shouldn’t you make other gods, but you shouldn’t worship your own peoplehood. I can’t believe I needed to tell you that.’

Other nations, though, do seem to worship themselves. It seems to be the norm. They either think their leaders are gods as in Egypt or think gods are simply to be manipulated for national ends, as in Midian. Our relationship is to be fundamentally different.

We have one more odd commandment. We are commanded to axe a donkey’s neck if it is not redeemed. This seems like a waste of a working animal, plus this Mitzvah was covered before. The key is in the choice of a donkey (instead of, for example, a horse) and the manner of death (axing the neck). The first born are tied back to the death of the first born in Egypt. The survival of our first born is a testament to this miracle and our connection to Hashem. When we redeem the first born, we recognize this connection and Hashem’s bringing us out of Egypt. The Jewish people were almost destroyed because we were stiff-necked. Then, we are rescued because we are stiff-necked. Our attribute of being stiff-necked is why we are still around today – despite everything the world has thrown at us. So what animal is most ‘stiff-necked’? The stubborn donkey. If we redeem it, then all is good. But if we fail to do so, then its neck should be axed. Our stiff neck might as well be broken if it is not used in the service of Hashem. I believe this command is brought up here for a second time, because it is relevant in a new and even more powerful way.

The final Aliyah seems strangely technical. Why mention that Moshe didn’t eat or drink? And why mention the procedure of the veil covering in such detail? Moshe spent his own spiritual capital standing up for his people. And that actually made his spiritual capital grow. It enabled him to see Hashem’s back. It enabled him to participate in the making of the tablets. But it also distanced him from the sinful people. Through his growth, Moshe has been insulated from all people (no eating or drinking) and specifically from the Jewish people who can’t even look at his spiritual greatness without fear for their own inadequacy. It is a divide that needs to be overcome for the idea of the nachal to become real. Where the design of the mishkan in the prior parshiot is a testament to our prior relationship, our actual building of the mishkan and the subtle differences we see in that building will serve as the tool that enables this new one.

In the fifth reading, Hashem says He will inscribe the tablets. But here, Moshe does it. From the simple text, it seems that there are different words on these tablets. Words of the covenant of distinction, rather than 10 sayings (Aseret Hadibrot). The role of building the divine relationship falls, increasingly, on us. And the action of building that relationship is what makes us distinct.

Before I leave, I want to talk about the concept of comfort.

In Shemot 32:14 Hashem reconsidered the evil He had said He would do to His people. The word for reconsidered is nachem. It normally translates as ‘comfort.’ It actually occurs multiple times in relation to G-d with this sort of translation. For example, just prior to the flood G-d “nachem” that he had made man on the earth and it grieved him to His heart. And just a bit later G-d says: “I will blot out man… because it nachems me that I have made them.” (excuse my Anglisized grammar, it is the only way for me to bring the words in English)

If we use the word as ‘comfort’, it seems to make little sense. Here, we’d read “And the Lord comforted on the evil that he said he would do to the nation.” In Bereshit we’d read: “And Hashem comforted because he had made man on the land and it grieved him to His heart.” and “I will blot out… because it comforts me that I have made them.”

How do you square these translations? How does reconsideration or regret get combined with comfort? The Torah uses this word at least four times to describe G-d seemingly changing his mind.

But in the middle parable of Bilaam, it explicitly says that Hashem does not do this.

“God is not a man, that He should lie; neither the son of man, that He should necham himself: when He hath said, will He not do it? or when He hath spoken, will He not make it good?”

The key to understanding all of this comes from that same parable. It says that Jacob does not have iniquity and so the Lord is with him. Because of the lack of iniquity, G-d doesn’t change his own mind and he doesn’t necham. But with iniquity, Hashem can necham. We can cause this change.

Which is why, immediately afterwards, the Moabites move on to encouraging sexual deviance.

It is their manipulative way of getting Hashem to necham and thus punish the people. Remember, they are divine manipulators

There is actually a beautiful and entirely made up form of Avodah Zarah that can square these meanings. This idea of comfort and reconsideration. In his pantheon, J.R.R. Tolkein has a goddess of mourning. What does she do? She turns sadness into wisdom.

Using this idea, nachem is an acquisition of a new perspective in the face of disappointment and loss. The connection is explicit in the story of the flood. “And G-d nachem because he had made man on the land and it grieved him to His heart.”

The heart is the source of our animation. Allegorically, it is the same to G-d.

When we are distressed, when we are overcome, we seize up. Exhaustion is a common sign of depression. Our change of heart is a sign of comfort. We get reanimated. We can reflexively change our own hearts (Esav does so by keeping in mind his plan to kill Jacob). Or, others can relieve that which is striking at our hearts (think of Isaac being comforted about the loss of his mother).

This is true comfort – it is deeper than just feeling better. It is understanding a path of action in response to a disappointing or tragic reality. It is also the kind of comfort that can lead to the flooding of the land.

It seems like Hashem can nacham in order to sustain morality and moral consistency.

So when Moses asks G-d to reconsider, he is asking Him to go to a state of agitation and regret. He is asking Hashem to channel the anger and disappointment and sadness into remembering to support the greater divine mission.

While there are clear later indications that this was always Hashem’s plan, Moshe’s very request is nonetheless a demonstration of Moshe’s deep deep wisdom.

With that, I’ll bring this episode to a close. As always, feel free to share the ideas – no attribution is needed.

Shabbat Shalom and thank you for listening.